(Taken from a blog entry published on the same date.)

Several weeks ago, I last wrote from a moment of waiting. I was hovering in an in-between space that felt like an atheist's purgatory, scrambling for a solution to get my bike across the Caribbean Sea, negotiating prices with airlines from the sticky tables of a backpacker hostel, where I was sleeping for $13 a night in a room with 12 bunk beds, all occupied by other travelers who were as restless as I was. The common area wall was covered in a gigantic hand-painted map, interrupted with food stains, peeling paint and graffiti tags, upon which you could project your own desires, wishing yourself off to another, less sweaty place.

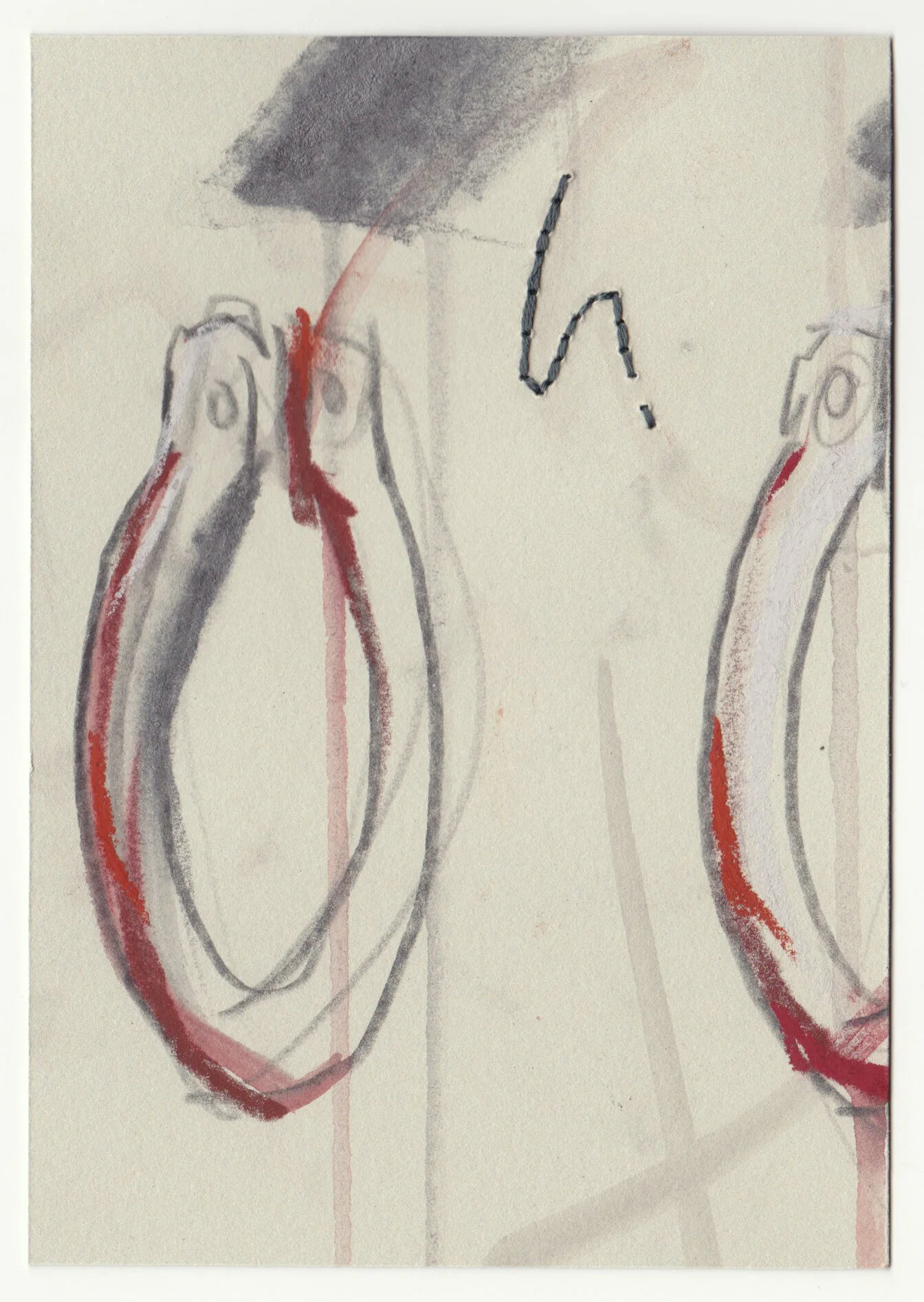

What Holds Us Together, series 2, no. 22. Graphite, ink, colored pencil and cotton floss on paper. 2020

Since then, my entire world has changed. I made it across the Darien Gap and into South America - currently poised at another crossing, hesitant to leave a country which has shown me more juxtaposed extremes than I can contain in my brain…though my body remembers it all. I have faced fears and proven some things to myself, while settling into a rhythm and routine that I've adopted steadily as a way of life. The challenges are basic, but vital:

How do you make resources stretch but still get decent quality sleep?

How do you deal with technical (i.e., motorcycle-related) problems yourself when you're used to being able to afford to pass them off to someone else with the proper skills?

How do you maintain your sanity when your local language skills are limited to purchasing gasoline, food and lodging for one to two nights? (And when at last encountering that English-speaker, how do you keep from blathering at them for hours, scaring them away, because you're so desperate for meaningful conversation?)…

.. and here's the real kicker:

How do you continue to be present... to keep appreciating all that you see, smell, hear, touch…while passing through the spectacles, beauties and horrors of the world, day after day, week after week, month after month? How do you keep it all from becoming, perceptually, a bit like strolling through Disneyland?

Every day I learn something new. A word of Spanish. A riding challenge, like how to cross a rocky stream or haul ass up a steep, rutted dirt road. And something will happen that'll remind me of life-long lessons. Like how to be patient. How not to force things, to let go of expectations. If I'm successful, then I avoid the Disneyland trap. Simple. Yet bloody complicated.

In the Panama City hostel, something amazing happened that changed the taste of my waiting from the bitterness of accepted disappointment to the elation of a realized dream. I learned that I could in fact sail across the Caribbean Sea with my motorcycle. The captain of a 60-foot steel-hulled vessel called the "Wildcard" agreed to take us both aboard, despite an alleged moratorium on the practice. This meant 5 days of turquoise waters, dolphins, encounters with indigenous Kuna islanders, sea sickness and the steady companionship of 16 total strangers, all for 2/3 the price of flying us both to Colombia.

... yeah ....

June 18

Portobello, Panama

The wait ended when I watched my 300-pound XT250 (aka Guera) get winched aboard the Wildcard in the old pirate town of Portobello. Five guys muscled her into a small outboard-powered lancha, holding her down by hand while motoring across the harbor to where the sailboat was anchored. Not once did she touch the water…and time sort of stopped dead for a bit as I watched her swing about in mid-air.

There we were. The Guera, me, two other (much larger) motorbikes, three crew members and 13 other passengers, all crammed together aboard a ship with two toilets, a kitchen (equipped with a propane stove mounted on pivots so that the teakettle wouldn’t go crashing to the floor when the boat rocked) and 18-odd berths the size and shape of caskets. Our shoes were stowed out of reach and there would be no bathing opportunities for five days other than those provided by the deep, salty-sweet blue-green Caribbean Sea. We were two Americans, two South Africans, one Colombian, one French, one Czech, two Swiss, two Germans, three Australians, and three Brits, all brought together through a common set of desires without any chance of escaping one another. It worked beautifully.

The first night was the hardest. “The sea was confused,” as our captain put it - alternating currents crashed into each other from opposite directions, forcing the boat into unnatural twisting patterns that sent many of us scrambling for the nearest toilet, queasiness exacerbated by celebratory shots of Panamanian rum and cheap beer. A canvas runner kept me from flying off my berth and onto my lovely male cabin mates below…a rude way to start any relationship. But gradually we all got used to the rhythm of the sea, and within a day I found it oddly comforting.

For three days we cruised in and out of technicolor postcard fantasy lands, a string of tiny islands covered in slinky curved palms, with sand so fine and white it ran through your toes like powdered milk. The islands were all part of the Kuna Yala, territory owned and governed by an indigenous group who have for centuries existed on these postage stamp-sized spaces, making houses out of palm fronds and living off of fish and occasional goods from the mainland. Our captain had a good relationship with them, knowing that many of us would buy artworks and other souvenirs in exchange for the privilege of spending time there.

But it could have been disastrous. The potential for human weakness to destroy such a thing was enormous: incompetence, petty behavior, intolerance, you name it. But we all got along, putting up with each others' bad smells and habits, swapping skin cells and basically loving every moment of it. The captain managed all of us efficiently and firmly but with kindness, laying down rules without ruling us, while his first mate cooked four delicious meals a day in a constantly rocking kitchen, risking slicing off fingers and worse with all the moving, flying instruments at hand.

Even the Kuna put up with us. They let us play with their kids while we ran around playing frisbee in their milky white sand, eating their rum-spiked coconuts, swimming in their tepid waters, drinking their warm canned beer. Yes, we bought their souvenirs. But we all got something much richer in return.

Our last night in the islands was spent with a family, drinking spiked coconut water next to a fire they built out of old palm fronds. I spent some time talking with the captain's friend Fidel, who was close to my age, whose kids cut the palm fronds for the fire and whose mother and wife made the brilliant tapestries from layered found fabric that they sold to make extra money. When I told him about my travels and art project, he wanted to know where my husband was. Why was I traveling alone, he wanted to know. It's a question I'm asked in every town I pass through, one that comes up in almost every conversation I have that goes beyond the casual pleasantries that get exchanged among strangers of different cultures. I never quite know how to answer it to their satisfaction. Someday I'll figure it out.

I enjoyed the conversation with Fidel enough to leave a piece for him and the three generations of his family on that island. I was in awe of his life, how rich but fragile it seemed from the outside. They lived off so little, making do with everything available, and it would only take one big wave to wash it all away…but the laugh lines in his face were so deep that perhaps none of that really mattered so much.

The final 24 hours of our voyage were long, simple, sweaty, sickly for some, boring for others. The boat rocked hard on the open sea. Some of us stayed in our births staving off sickness; the rest of us hung out on deck, splayed out horizontally on polyester cushions, trying every once in awhile to play cards, and generally failing. Though it was necessary to drink lots of water, you didn't want to because it meant having to fight your way down to one of the heads, risking getting thrown into some sharp object or other in the process. But we moved fast and by 2am the morning of June 23 we were anchored in Cartegena Harbor.