** Published in RideApart motorcycle magazine March 26, 2017; based on an In Search of the Frightening and Beautiful blog entry written in 2014. **

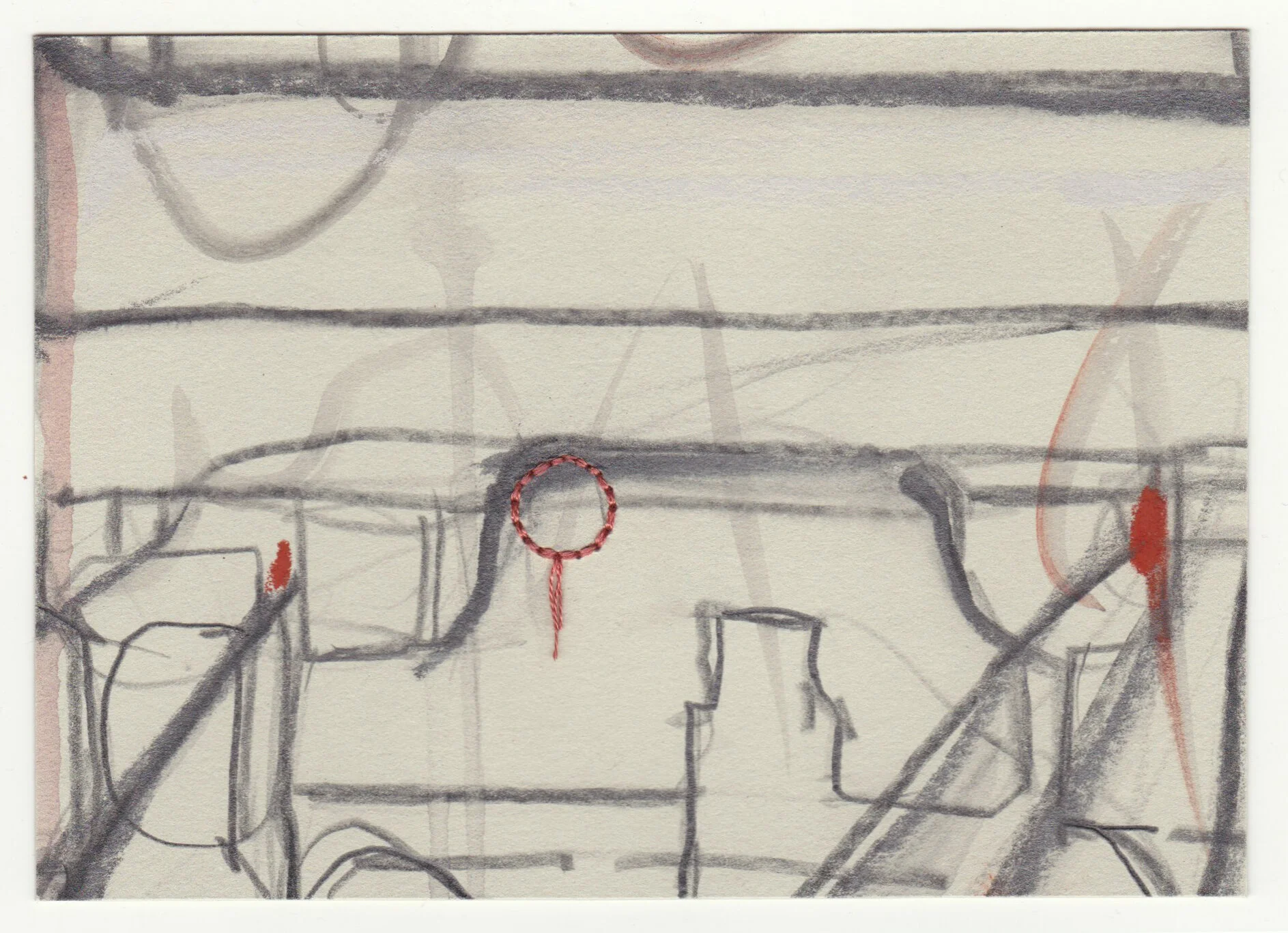

What Holds Us Together, series 3, no. 19. Graphite, pastel and cotton floss on paper. 2020

“Don’t you know that’s a machete country?”

It was an exceptionally grey, sweaty Houston morning, and my overloaded Tiger’s side stand dug an impression into the soft asphalt in front of the copy shop where I was trying to laminate some fake IDs. My polyester running shirt clung to my back under my heavy armored gear as I mumbled a response to his question, knowing full well I was asking him to do something illegal.

“I don’t know anything about machetes, but these might keep me from handing my real license over to corrupt cops…”. The shop manager cocked an eyebrow and looked me up and down. I could feel my face and ears burning, and my throat tightened. God, did I feel stupid.

With three crisp, crooked-cut, inkjet-printed licenses ready to be whipped from my “fake” wallet on demand, I filtered through rush hour traffic, heading southwest. I avoided the Shell station attendant’s cold stare from behind inch-thick plexi as I paid for that last tank of Houston gas, a look that became fiercer in my head as Hwy 90 rolled out toward McAllen, Texas. Tomorrow I’d enter Mexico for the first time, for an ongoing art project and motorcycle journey I call “In Search of the Frightening and Beautiful”. I had no idea what I was in for, and the closer I got to the border, the harsher the stories (and the judgment) became.

What Holds Us Together, series 2, no. 25. Graphite, ink, colored pencil and cotton floss on paper. 2020

Just a few weeks earlier, I’d left New Jersey for good. I quit my job, ended an 8-year relationship, sold or stored everything, got on my bike and took off south. It’d been one of the harshest east coast winters on record, but with heated gloves and a break in sub-freezing winds, I dodged ice patches and filth-crusted snow piles, exiting the scene, hell-bent on living nomadically and eating up as much of the world as possible.

It was an invitation into the unknown that did it. A suggestion planted by a sharp-eyed, soft-spoken gentleman who liked my artwork. His confidence in me fueled a quest for sponsorships, a crowd-funding campaign and a 16,000 km solo loop around the United States for the sake of art and a yearning for a certain kind of freedom – terms I still live by today.

I make embroideries by hand: slowly crafted, detailed renderings of motorcycle parts with words describing things I’ve seen on the road. The bike components are like body parts – as only they could be, given how the machines built from them respond to every corporeal movement of their riders, carrying them swiftly through time and space. I leave them in places I pass through for others to find: a kind of trail of evidence, gifted back to the world in a spirit of exchange. I take photographs, have conversations, see and learn new things – and leave a piece of myself behind, in the form of a precious thing that takes a lot of time to make.

The embroideries are a gateway. They’re a kind of pass, a way into and justification for entering places I don’t belong. I stitch them enroute, out in the world, as invitations to conversations. The road breeds loneliness; I’d discover later how valuable a tool this can be for overcoming it.

So there I was. Tiny, blond, blue-eyed, with breasts, equipped with two months of Rosetta Stone Spanish and mediocre dirt riding skills, aboard a 225kg Triumph Tiger 800, gunning toward what was then my greatest unknown: Mexico. I’d accumulated miles and overcome challenges, learning of strengths I never knew I possessed… but all inside the borders of a country defined by speech patterns and unwritten rules I knew too well.

What the hell was I thinking? In McAllen, American flags along a boulevard of car dealerships waved furiously in the wind whipping up over the Rio Grande. A towering police beacon screamed silently in the nearby AutoZone parking lot, with its panoramic surveillance cameras and red and blue flashing lights. “You stupid girl..”…

At 7 am the next morning, the Anzalduas Bridge was empty. Long, low, flat and sparkling clean, its thick concrete median ruled out turning around. I crept across slowly enough to stare down at the steel border fence north of the trickle of sludge remaining of the Rio Grande, letting my imagination linger in the half-built cinderblock shacks that began appearing on the other side. My heart pounded like a jackhammer inside my chest. There wasn’t any going back now.

Signs…everywhere. Ones I couldn’t understand, in cold blue institutional capitals. Gigantic half-spherical plastic-coated speed bumps threatened a wipeout if I veered in the wrong direction. And there were guys with guns - big ones. They waited in desert fatigues to inspect fools like me wanting to enter their country, to extract any objects or substances of ill-intent. They stepped directly in my path.

The next 5 minutes unfolded in a series of pantomimes, clumsy gestures between individuals with vastly different backgrounds unable to communicate in spoken words. I climbed down from my oversized bike and stood next to it, like some miniature astronaut posed next to a spaceship. I took off my helmet. Their eyes lit up and they laughed. They were young enough to be my sons.

After proving myself harmless, they gently pointed me in the right direction, back toward immigration and customs, to acquire all the permits I needed to ride through what would turn out to be a wild, crazy, unbelievably beautiful country.

No one touched my over-packed bike in the parking lot. An older man, who could tell I was still lost, came out to greet and lead me to the immigration desk. He even found an English speaker who guided me through all the steps needed to ride legally through Mexico. Yeah, there were a few idle-looking men hanging around, seeming bored, whom I noticed when I was finally done. Maybe they were after jobs – who knows. But they didn’t mess with me. They just smiled and shook their heads as I climbed back on my bike and took off.

I rode hard and fast the rest of that day, through poverty-stricken towns with pastel-painted store fronts, past brightly-colored memorials for people killed in car accidents, through aromatic orange groves and over feces-saturated rivers, into mountain ranges so steep and lovely they took my breath away.

That was three years ago. Since then I’ve crossed 13 other Latin American borders, making it to Argentina, from Houston, TX, solo. I’ve left 45 pieces of art in the landscape and in peoples’ hands, throughout the Americas. I’ve had experiences so rich I can only hope to describe them here. This is the beginning.