(Originally published in RideApart online motorcycle magazine August 7, 2017)

The XT sat in the intensifying sun, its white plastic bodywork glistening like sweat. It leaned on its side stand as though it were a crutch, bearing its weight like a champion despite some great odds. I wondered how fast the motorcycle would topple over if I’d parked it on something other than concrete.

It was time to go. Friends were waiting 15 miles up the road to send me off into the greatest of unknowns I had till that point faced…an unknown for which I had inevitably over-packed.

A mason jar-load of saved up coins…check. Chris Scott’s Trailblazer guide to adventure motorcycling…check. A five-pound pre-lubed spare chain, extra tubes and an uncanny number of redundant tools…check. A complete collection of camping equipment bungie-strapped to the bike’s ass-end (check!), which together had transformed my sure-footed little 25occ dirt bike into one of those sad Grand Canyon donkeys forced into slave labor for the callous pleasure of tourists.

The setting sun pierced my squinting eyelids as I steadied the persistent wobble such weight placed on the bike at speed. 60mph was as fast as it could go – downhill and with the wind at my back – and it wasn’t happy there. Less happy were the Hwy 62 drivers used to blazing down the ill-reputed desert straightaway unfettered; their wind wakes made the XT’s handling that much worse.

Yeah, the weight was dangerous…but I had worked damned hard for every ounce of it.

December 2014

Why was I so gun-ho to get to South America? What obscenely restless fire burned so hot that I would succumb to such a notion, all hundred pounds of me, blue eyes, blond hair, with lily white melanoma-prone skin, next to no Spanish and lacking pretty much everything but a pot to piss in?

The metaphorical grace of taking my project, In Search of the Frightening and Beautiful, across more distant, difficult thresholds and into lesser-known-to-me territories was the most obvious, public reason. Perhaps it was also the very absurdity of the idea itself that was so appealing: a desire to challenge its immediate, obvious dismissal – by others, for certain, but also as a way to grapple with my own self-doubt. In any case, it wasn’t a question of “wanting” to do it. It was a matter of need. I was going and absolutely nothing was to stop me. This was my frame of mind.

So, then…how does one find the resources necessary to embark upon a transcontinental art project and solo motorcycle trip? Do they just fall out of the sky? Or can you somehow squeeze out that extra year’s salary washing dishes for a few more hours per week?

Me - I got lucky with timing, the generosity of damned good friends, and the faith of some pretty amazing strangers. It also didn’t hurt that I worked my ass off.

After sketching out an ideal route, the first step was to figure out how much I needed, for everything from bike prep and spare parts to insurance and border crossing costs. I knew food and lodging would be reasonable based on how much I’d spent the previous summer traveling through Mexico. I had to factor in getting around the Darien Gap (the jungle-choked break in the Pan American Highway overlapping the Colombian and Panamanian borders previously navigated by a mere handful of folks, generally well armed and able-bodied enough to port vehicles and supplies on their backs), as well as shipping the bike home from Buenos Aires at the end.

It added up to close to US$20,000 (which I’d later learn was conservative), a tidy sum for an artist used to living on part time wages and occasional art sales. But I already had a book planned and a pledge from my mother that’d cover most of its production costs…so I went to work.

T-shirts, posters, mini-cards and 5-by-7-inch prints all fueled a crowd funding campaign that got me started. I had a blast designing all of these things and shipping them out to campaign contributors from the little cinderblock desert cabin I rented for $200 a month. From a 5-year-old laptop on a worktable with a broken leg, I produced an identity for a concept that’s ruled my life ever since.

The book, pocket-sized with 112 image-packed pages documenting two earlier journeys through the United States and Mexico, formed the coup-de-grace. It had no text other than an essay describing ISFB and its intentions, but the pictures themselves did the job, creating tensions, impressions and hidden meanings meant to convey the essence of the project as a whole. Musician friends helped me throw a launch party and fundraiser attended by folks from all over the desert, effectively raising over $1000 alone. My filmmaker pal Eva Soltes directed the campaign video, eloquently summarizing the project and its objective in less than 3 minutes.

The campaign itself pulled in $6665. Not nearly enough. I would have taken my chances and gone anyway, perhaps making it as far as Guatemala. But then something outrageous happened.

Two old friends whom I’d known well years before were paying attention. They were organizing projects for an artists’ residency program and exhibition space in Houston, Texas (U.S.) called Cherryhurst House. Together we talked about how In Search of the Frightening and Beautiful could fit within Cherryhurst House’s programming. The journey, its premise of leaving behind or giving artworks along the way, the potential for me to bring back ideas from people with different cultural backgrounds and life experiences, and to share that knowledge in the form of new art work – these were possibilities that excited us all.

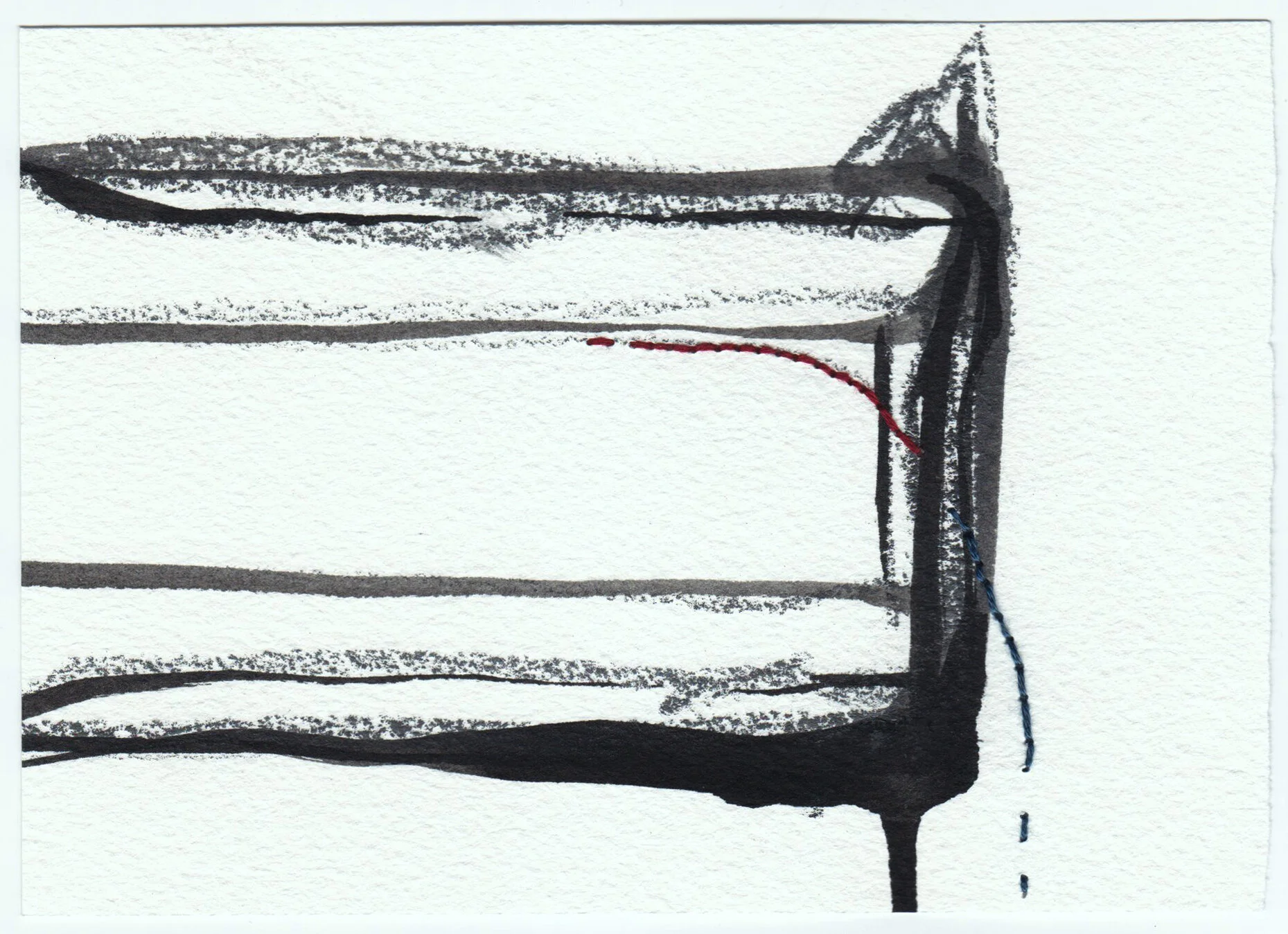

In January 2015, Cherryhurst House placed ISFB on its residency schedule for the following year and acquired an artwork of mine for its collection valued at enough to cover over ¾ of the costs needed for the entire trip. The piece – a nearly half-to-scale hand-stitched rendering of Ripley, my beautiful former 2012 Tiger 800 – is appropriately titled Triumph.

March 2015

“Ok, what can we help you lose here?”

I was late…and nervous. I’d stopped at the grocery store to get rid of the coins.

They’d weighed my backpack down so much that its straps had dug trenches into my jacket’s armor, cutting off the circulation in my shoulders. But my friends were still waiting at our favorite gathering place (our “church for atheists” as we affectionately call it), a little roadhouse in the middle of the desert better known as “The Palms”.

“That….” Kip pointed to the 5-pound spare chain. “It’s a Japanese bike; you can find spares for that thing anywhere… and it’ll be here waiting for you when you get back.” He gently shoved the greasy box containing the brand new $120 custom-cut part into his bag.

“I can scan those pages for you and email the PDF,” said Maryrose, tossing my heavy guidebook to the ground.

Bernard, Eva, Kip, Brian, Maryrose, Tim, Rebecca, Laura, Mary and James, Hannah, Billy and me…together we rifled through my packing job, stripping the XT down to its bare essentials, so that I’d at least have a modest shot at getting out of the desert without crashing. I still had sand to traverse on my way east, making the unnecessary weight all the more precarious. My friends were looking after me. It wouldn’t be long before I’d realize just how important that moral support is.

It was 11am before I was finally pointed toward Houston, the first official stop on my path, where a kickoff event was being planned. That night I wanted to make Wickenburg, Arizona, 220 miles east on a zig-zag of back roads I thought my little thumper could handle. The sun blazed directly overhead and the heat was already intense. Cheap sunscreen stung the corners of my eyes.

Ironage Road, a 20-mile stretch of dirt connecting Amboy Road to the main route east, seemed like an appropriately challenging start. “Shit, I ride a dirt bike,” I thought. The sand in front of my cabin was deeper, so I figured it’d be no problem. But since it was already mid-day and I knew the soft stuff would slow me down, I took Shelton instead, a 3-mile shortcut across the valley to Hwy 62. It was easier sand, better graded and more predictable. Or so I thought.

“Confidence comes with experience…” … and the caffeine of several cups of coffee…

At 2.5 miles down Shelton I could already see the sun glinting off the hoods of cars speeding along 62. “This thing is happening,” I thought to myself in half-disbelief, so filled with euphoria that the entire horizon literally sparkled.

It was the very moment I thought nothing could stop me when I saw the soft patch in the road. Within the next, the bike was on top of me, facing backward, pinning my foot into ground, its still-too-ample weight crushing it like a beer can. I don’t remember how I pulled myself out from under it. But I did. The pain is something I’ll never forget.

So… ISFB journey number 3, edition 2015 – destined, supposedly, for the bottom of the world – was off to a great start. My foot wasn’t broken (I could walk around on it) but it hurt like bloody hell. I absolutely refused to call up Kip, who’d scoop me up with his van in a red hot second if asked.

“I really don’t know what the hell I’m doing,” I thought. “But I’m going to do it anyway.”

Slowly I pulled the gear off the XT, that which wasn’t already scattered around, decorating the sand in primary colors. It took me three tries to get that bike off the ground. But her bars were still straight and her tiny single cylinder still fired up, despite being flooded with gas.

Re-loaded and pointed east, we limped across the desert, my “Guera” and I. Two stubborn white girls… there was no stopping us.