(Excerpt from the blog entry, My Own Fantastic Heart of Darkness, Part 2, posted June 2, 2015.)

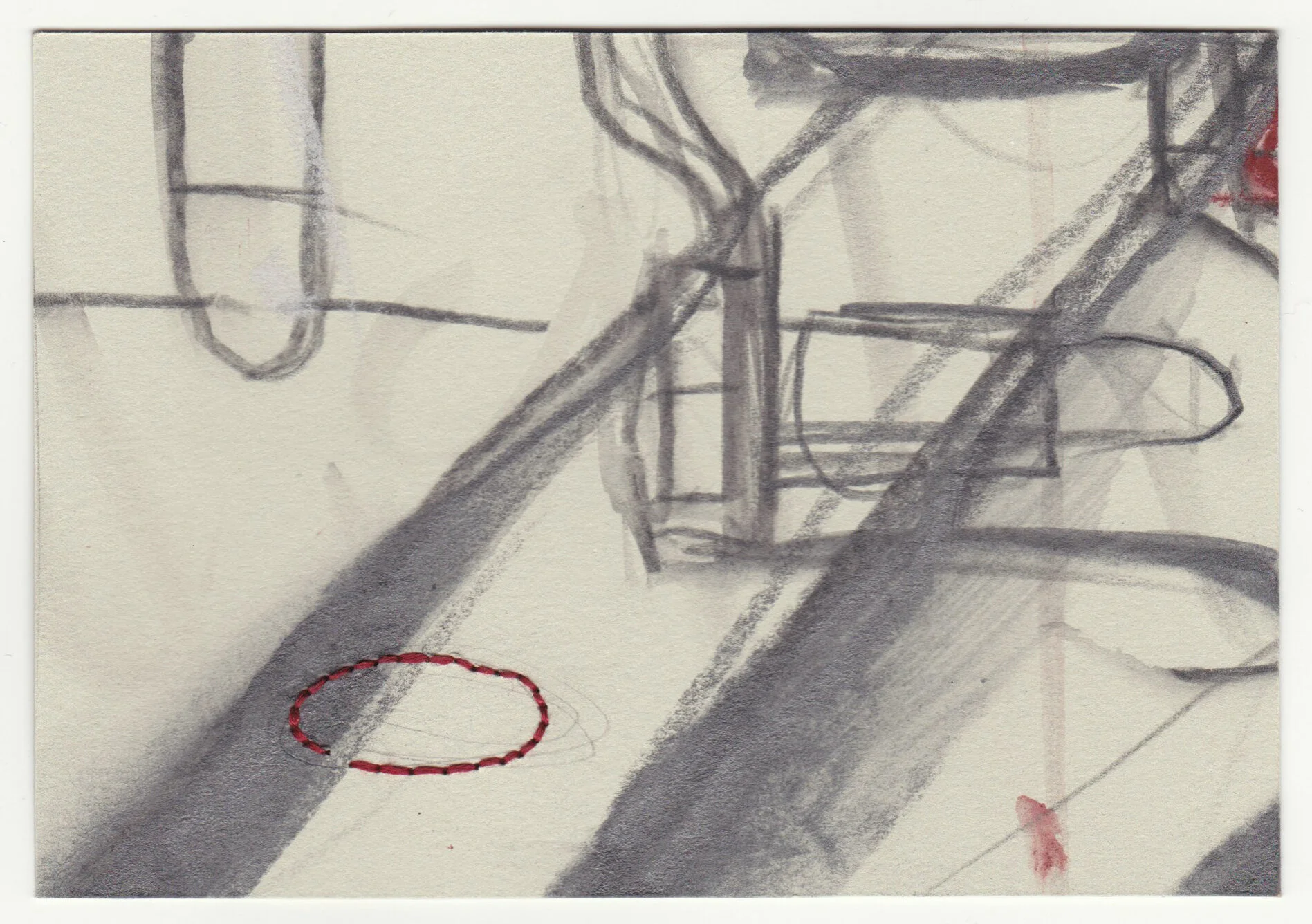

What Holds Us Together, series 3, no. 24. Graphite, pastel and cotton floss on paper. 2020

On April 26 I pressed on, following a route into the eastern part of the country toward Quetzaltenango (aka Xela), where a friend awaited, along with a trusted mechanic who would give my bike the rather large amount of attention it needed. I thought I could make it in one day.. but I was mistaken.

The road south out of Cobán is paved, twisted and delicious, winding through jungle mountain canyons clustered with thatched roof towns and cliffs that block out the sun. To get to Xela, I had two choices: ride through Guatemala City, reputed to be traffic choked and one of the most dangerous in Central America; or take a smaller route west through the mountains and more indigenous villages to Huehuetenango, then south again to Xela. I chose the latter.

San Cristobal Verapaz is a smallish grid of dirt roads and occasional cobblestones situated above a lake. The road leading out looks just like the others, and without street signs it's easy to get turned around. I asked a couple of kids walking toward me where to go, and the map they drew in the sand worked better than any GPS. And of course, there were the buses. I've since learned that the best way to suss out the way in and/or out of a town is to follow the collectivos. They've yet to let me down.

Graded gravel wound gently in easy sweeps at first. Then the road ascended, gradually getting steeper, with sharpening switchbacks and a drop-off rivaling the cliff in the celebratory-cum-tragic ending of the film Thelma and Louise. Then it started going down. And down. Narrowing, loosening, with bigger ruts and rocks, sandy washouts, and yeah... buses.. trucks.. and other motorcyclists on 125's, zooming up and down the thing as they'd likely been doing most of their lives. Little villages lined the road in places, with huts made of board and thatch clinging to the hillsides, women in hand-embroidered dresses carrying enormous loads on their heads. All witnessed through heavy clouds of white dust.

Eventually, after 15 or 20 miles, the asphalt came back, first in patches, then gradually in larger sections, till it resembled a paved road, but with occasional lane-sized chunks missing to keep me on my toes. A friend of mine said, not so long ago,

"You never, ever ride at night down here." True that, luv.

Late that afternoon, I found an empty bus stop on the road side, with a thumbs-up sign painted on one end and a skinny cow standing on the hill behind it, looking down with a dull gaze. Without thinking, I pulled over and dug into my tail bag for a piece to place on the bench. I knew it would be found there, quickly.

And it was. By a man who owned the land behind the stop, who saw me place it there. Santos Gamino had a warm smile; his curiosity was open and genuine. He wanted to know what I was doing, what the object was I'd put there, and for the first time, I had the opportunity to actually present someone with one of my embroideries. I tried, hard, to explain In Search of the Frightening & Beautiful to him in Spanish. I don't know how much of what I said he understood…but I did get across that it was a gift. For him. And he thanked me for it.

I didn't make it to Xela that day. Instead, I landed in Sacapulas. With mountain cliffs scarred by mining operations and sunsets made brilliant by the ever-present wood smoke. I crossed a bridge made from a patch job of riveted steel plates that dumped me into a small chaotic square filled with 3 wheeled Bajaj Chetak taxi scooters ("tuk tuks") and stationed collectivos from neighboring villages. The town crawls up the hillsides and trash is everywhere, dusty, faded and collected in corners. I found a hotel with a $6 bed, a refreshingly cold shower, a fan, and place to lock up my bike behind a 7-foot solid black metal gate.

Sacapulas felt dark to me from the moment I crossed the bridge. People had shadows across their faces. I instinctively knew not to go out here at night. A gut reaction based on my own projections and biases? Quite possibly. But I'd come to find out details later about this place that confirmed my feelings - like the fact that there's no food here, really. Just chicken parts. Tortillas. Some bruised, moldy tomatoes and mangoes. And a enormous selection of bagged snacks that hung floor to ceiling from metal fixtures in tiendas that lined the streets (all of which sold the same things).

I'd only intended to spend one night. I had some dinner and worked on an embroidery on the terrace upstairs. A couple of young local women hanging out there invited me to join them for a beer or two, and I was tired and more than happy to oblige. We communicated mostly in made-up sign language, listened to their music and I heard about their boyfriend troubles (of which I could understand maybe 10%). They uplifted my spirits, and for the moment my perceptions changed.

The next morning, my laptop was gone. The following 15 hours were some of the strangest I've ever experienced.

I explained the situation to the owner of the hotel and asked where the police station was so I could file a report to make an insurance claim. I assumed I'd never see the computer again and was already plotting my survival strategy for the rest of this trip without it. The hotel owner (Roxana), enraged, took me to the station herself and started making phone calls... lots and lots of phone calls. She knew where the girls lived...

... and after 15 hours of waiting in municipal offices, I had my computer back.

Because of the efforts of Roxana, the police and the justice of the peace in Sacapulas, it is not an exaggeration to say that this entire trip and project was saved. I am a white American tourist. Would an impoverished indigenous local have gotten the same treatment? Probably not. But I can only speculate, and I'm sick of speculations. These people showed me empathy, humor and kindness, and they worked damned hard to make the situation right. No one asked me for so much as a dime in return.