(From a blog entry of the same title posted October 16, 2015.)

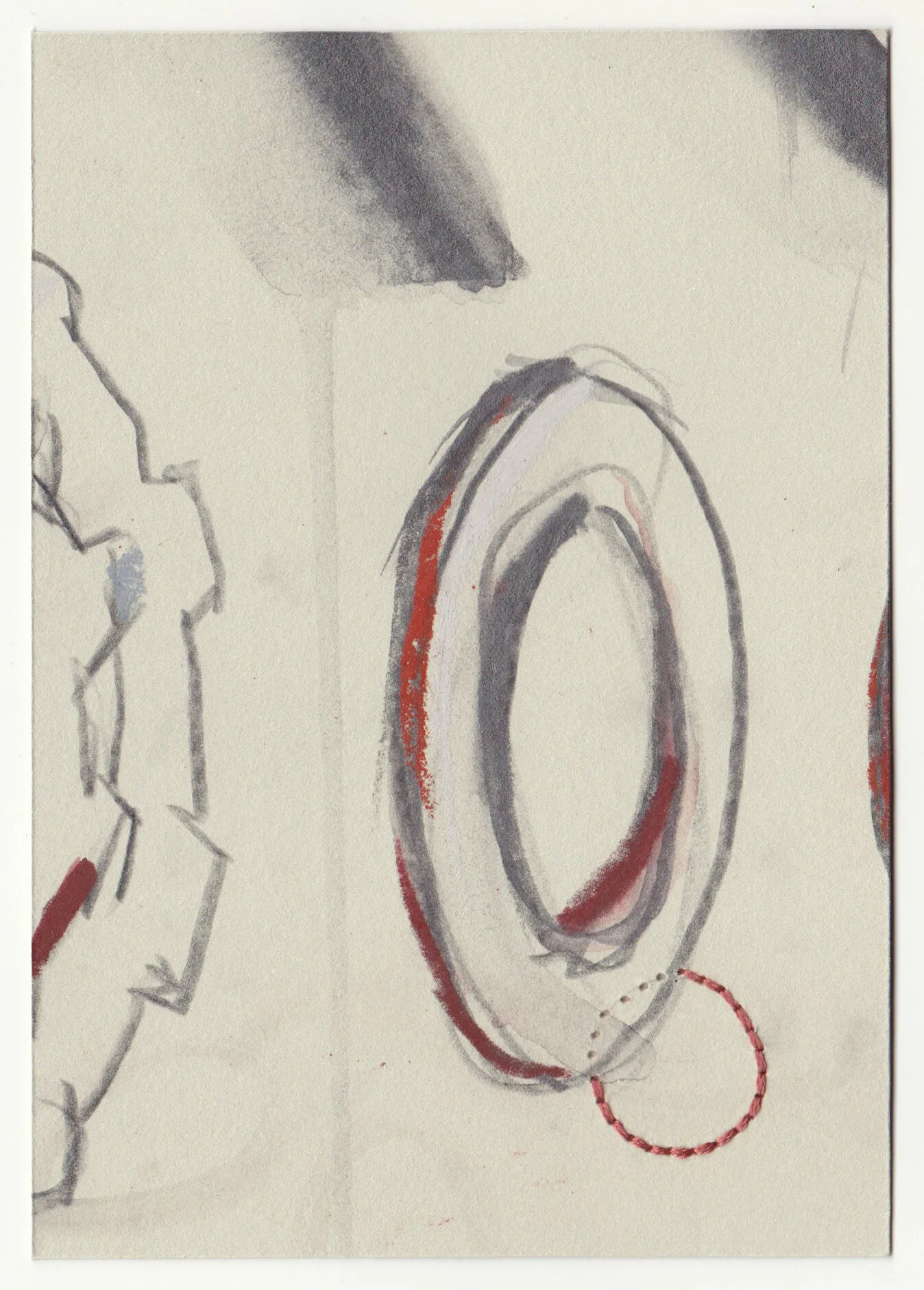

What Holds Us Together, series 3, no. 26. Graphite, pastel and cotton floss on paper. 2020

Sidelong glances.

Cracked foundations.

Terra-cotta tile roofs underlaid with corrugated tin and blue plastic tarps, covered in used tires that keep it all from blowing away in the storms that blast up over Lake Titicaca and cast down sheet rain and nail-sharp hail pellets, turning the narrow streets into swift two-foot currents.

From the corner room on the third floor of this hospedaje, I can hear a man playing his plastic recorder, badly, with skin-covered stumps for hands. An old guy peddling mysterious chocolate and avocado-colored liquids in clear 5-gallon buckets, serenading their deliciousness in a gravelly, nasal voice. School kids squealing with joy to patriotic Peruvian anthems resembling Nazi death march songs.

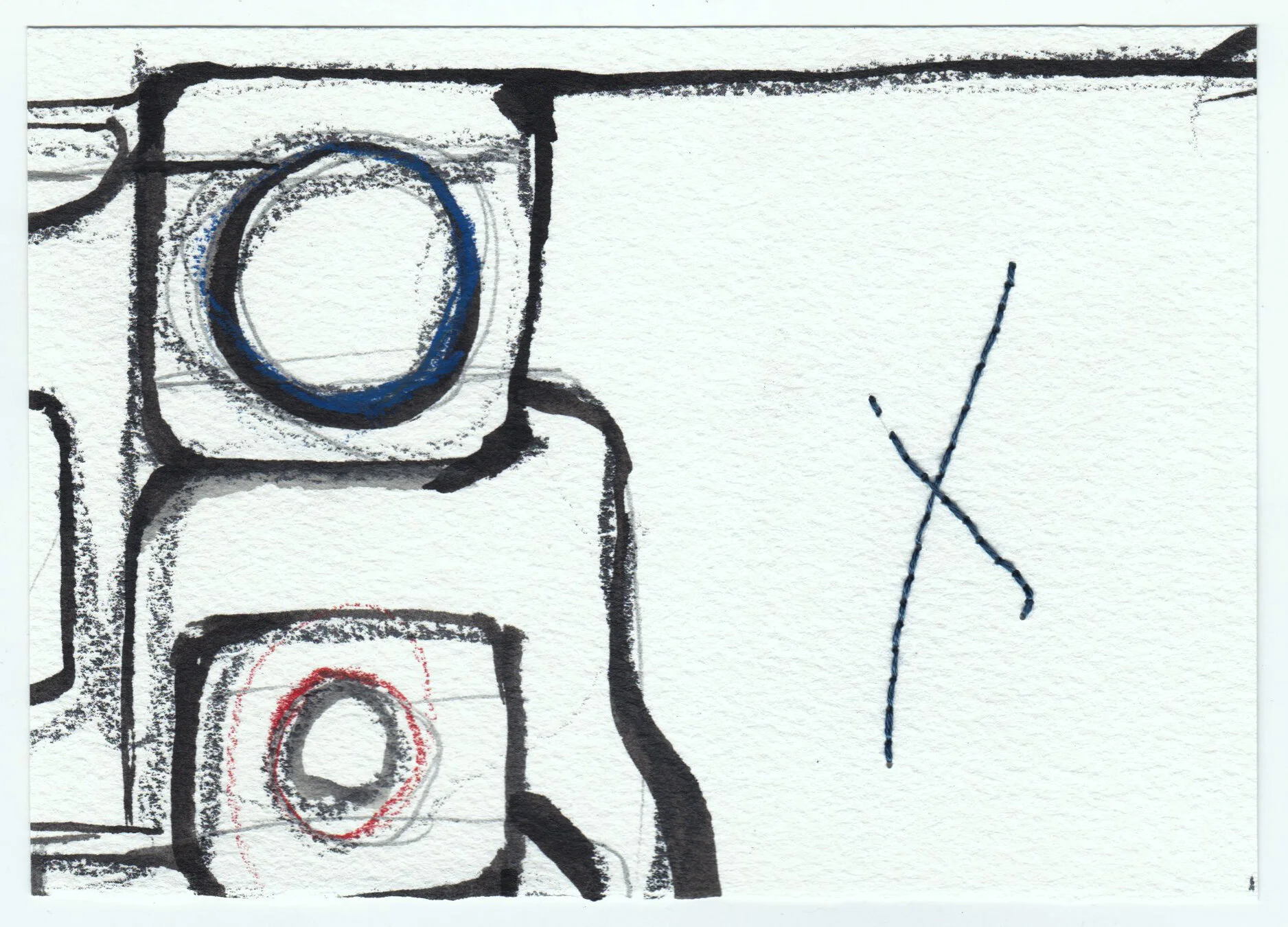

What Holds Us Together, series 2, no. 17. Graphite, ink, colored pencil and cotton floss on paper. 4.25x6”. 2020

I've been in Puno now for over a month, which is plenty of time to record its pulse, its smells, its habits. Its people are still elusive to me, as they'd remain even if I lived here for the next fifteen years. But I've taken great pleasure in watching, like a blond speechless fly on the wall.

There's the usual tension between tourists and locals, seemingly overridden by endless streams of parades, where folks from Puno and elsewhere descend upon the streets in obscenely colored homemade finery, busting out rhythmically to hand-painted base drums and pan flutes, taking cell phone pictures of each other, while doe-eyed Americans and Europeans look on, armed with point-and-shoot flash cameras, not knowing what else to do with themselves. They flit in and out of shops selling alpaca hats and sweaters, then disappear into their 3-star hotels.

Then there are the folks who belong to the corners, whose movements and utterances define the neighborhood as regularly as well-maintained church clocks. A lady wearing six wool hats, who drags a plastic stool down the main tourist street at a snail's pace, creeping over a bent cane to some mystery location who knows how far away. A gentleman with acid-washed jeans, polarized shades, 4-foot amps and a Perry Como voice whose lounge tunes soothe away the honking of taxis and tuk-tuks perpetually clogging the streets. Uniformed school kids take over at 2pm, laughing, holding hands, playing tricks on each other. Cops in tight black pants watch over it all.

What does it mean to me on the move, more-or-less constantly for 6 months, then stop dead in your tracks? Well, for one thing, your body catches up, going into a bit of shock from the rest it's no longer used to getting. Germs lurking in lungs or joints creep out to take advantage of a quieter body to attack. You de-toxify (assuming you're not spending all your time eating vast quantities of potato chips and chocolate while watching Spanish language infomercials and downloaded films from under 60-odd pounds of stacked Peruvian wool blankets). You sleep. You think (perhaps too much). And you wander the same streets every day, recording the stuff that gets overlooked. The shadows and fleeting gestures. The street trash. The reflections in windows, on the ground and occasionally, in people's faces.

I have this new pattern of existence that's entirely my own, governed only by the weather and some rather unique circumstances, as well as those of a friend with whom I've been spending time. It's all about waiting and learning how to extract quality experiences from what is both extraordinary and mundane. Time passes like a ticking bomb while we witness the same parades, the same restaurant criers, the same tamale ladies whose shrill, guttural voices you can set your watch by, morning, noon and night. Life is not unlike the movie "Groundhog Day". I wake up at 6:29 every morning and the rising sun casts the same golden light in the same direction, at the same moment through the same machine-embroidered curtains.

In what direction will I walk next? Will it present anything new? Some fresh obscene graffiti, discarded trash or human poop never smelled before? Will the ever-present raw brick unfinished facades reveal some new story about their anticipated, permanently absent residents? Will I ever leave this place?

Yeah. I will. It's just a matter of extracting myself from a womb of sorts. A comfort zone that has some seductive-destructive qualities. I could get lost here... but I have to refuse…

10/10/15

The microscopic bugs squirming around my intestines are (presumably/hopefully/God willing) dead. A week ago, I submitted a tidy plastic vial of yellow liquid poo to a blue uniformed woman in a room whose fluorescent-lighted walls were covered, floor to ceiling, in red lettered lists of microbes. For 7 soles (about US$2), you can have your stool examined. Mine turned up with Giardia (and E. Coli).

But the gurgling guts and intense need to sleep, thanks to 6 days of the aptly-named drug "Flagyl", have tapered off, and I can now face a standard-issue Peruvian plate of meat, rice and potatoes without turning green. And in a few days, I'll have a replacement for my stolen bike title, so I can enter other countries semi-legally. Hallelujah..

In the meantime, I write, think, plan, make stuff. Pouring through the photos I've taken, pondering what they'll eventually become. Around the corner there's a little tienda that sells paper, pencils, school notebooks and Hello Kitty stickers. There I found some thick paper and pencils with lead soft enough to smear around, and I'm churning out sloppy drawings like a kid with a set of finger paints. It's a welcome break from the neat, tidy, repetitive stitches that go into each embroidery. It feels good.

Time is ticking away… and my money is too. I have enough to get to Buenos Aires, but that's about it. Though I'm spending next to nothing to be here, and it's still witch's tit cold in the Uyuni Salt Flats, very soon I will have to haul ass.

Bolivia awaits. I understand it to be the most desolate, remote and logistically difficult country I'm to encounter on this journey so far. They've got a gringo tax on gasoline, where blondies pay triple the price, in territory remote enough to cause someone with a 2-gallon gas tank some serious concern. And there's sand. Soft patches with washouts that promise ruby-red lake vistas with huge populations of flamingoes. Do I want to risk another near-broken foot for a flock of birds?

Maybe…

10/14/15

This afternoon my friend and I went wandering through a hospital. Outside, the weed-choked grass and cracked concrete make it look closed. Inside there are scratched murals, dead electrical circuits, broken windows with thick dust and curled, used tissues left on their sills, bleached from the sunlight. People linger in the dark hallways near the emergency room, waiting for help or news of their friends or family inside. The sick are draped in thick wool blankets - the same kind I've been sleeping under for two months - and the same kind in which orderlies wrap the dead.