The thin trickle of scorching water drips down my body and collects at the drain near my toes. The ever-thickening mass of hair on my head - now rivaling Ronald McDonald's - absorbs most while the rest runs over my face, blurring my vision and sharpening my memory and imagination.

In the stall next door some poor sonofabitch is wretching his guts up as a result of last night's mixed toxin binge, or from some unfortunate batch of muy picante taco meat from the little joint with the greasy chairs and tables a few blocks away. As his toilet bowl echoes from the sound of repeated spitting, a swirling mass of hand drawn images spins in my brain, collected from the walls of my hostel room, neon pink spotted pigs, pregnant women with penises, children with space-age ray guns and other acid-induced pictures and proclamations: several years of spot-on insanity all layered into one psychedelic tapestry bleeding into my experience of this entire city.

One month has gone like a puff of smoke. Disintegrated into grimy storefront window reflections and peeling post-colonial surfaces, slick with oily acid rain, where late 60s exhaust-belching Dodge passenger busses wear half pipe grooves into heavy, hand cut cobblestone streets. Thousands of red brick structures coat the insides of this enormous 12,000-foot-high canyon that is the bedrock of La Paz. They rise up into the clouds so that at night I'm surrounded by walls of glowing white lights.

It's hard to breathe. But the streets give me energy, enough to climb these hills that are so high I get dizzy. The higher you go, the narrower they get, and the markets begin taking over. Stalls covered in bright plastic tarps consume so much space that before long you are squeezing your body through drapes of hanging sweaters, meat dripping from hooks, between piles of used toys, pots and pans, or overripe fruit. Sweat and sex saturate the atmosphere, despite Catholic overtones and temperatures that make my teeth chatter. You can smell it in the air.

I've gotten to know the pavement cracks intimately here. They criss-cross stone sidewalks so steep they need stairs. If you want you can climb the all the way to the top of the mountain, where the poorest people live. It's cheaper up there because it's a pain in the ass to get to and it's bitter cold. (But hell... at least the views are really something.)

Monday mornings the shuttered city of Sunday springs back to life. As I sip on a "distillado con crema", semi-spiked with some unknown hooch, a group of 10 people fill the Torino Cafe with voices, clapping, the strumming of a mandolin and guitars. They are smartly dressed in black suits and sing of broken hearts while blending in nicely to the wood paneling, lamp light and collections of English language pulp fiction novels, all dog-eared and spine cracked, that line the shelves of this darkened space that was probably once frequented by Nazi fugitives. No one smokes in here, but the walls are stained from cigarettes past.

When I'm done with my coffee, I'll walk down the hill in search of ladies selling avocados, tomatoes and triangular-shaped bread, ladies with gigantic ruffled skirts and ill-fitting bowler hats who spend so many hours selling their wares on street corners that they often fall asleep, deep lines impressed in their cheeks making them look older than they really are. Police in riot gear sweep around corners on Honda 250cc dirt bikes spray-painted military green. And people clog the narrow, slippery sidewalks, moving like confused bees at a million different paces, bumping into each other, narrowly avoiding annihilation by collectivos all jockeying for street space and customers in the bottom of the canyon.

La Paz has its dark spots. The market merchants don't suffer gringos gladly, charging us twice as much for goods as locals, assuming we're rich and can afford whatever price is asked. Sometimes you see effigies hanging from telephone poles, jeans and hoodie-clad "bodies" stuffed with rags, signs to would-be criminals that offenders will be strung up or burned, and not by the police. Young men who try to make a living shining shoes cover their faces with ski masks to avoid being stigmatized. And far too often women spend their final years sitting on filthy sidewalks, hawking several varieties of dried potato, only to have to climb to their hilltop homes every night with sacks of unsold merchandise on their backs.

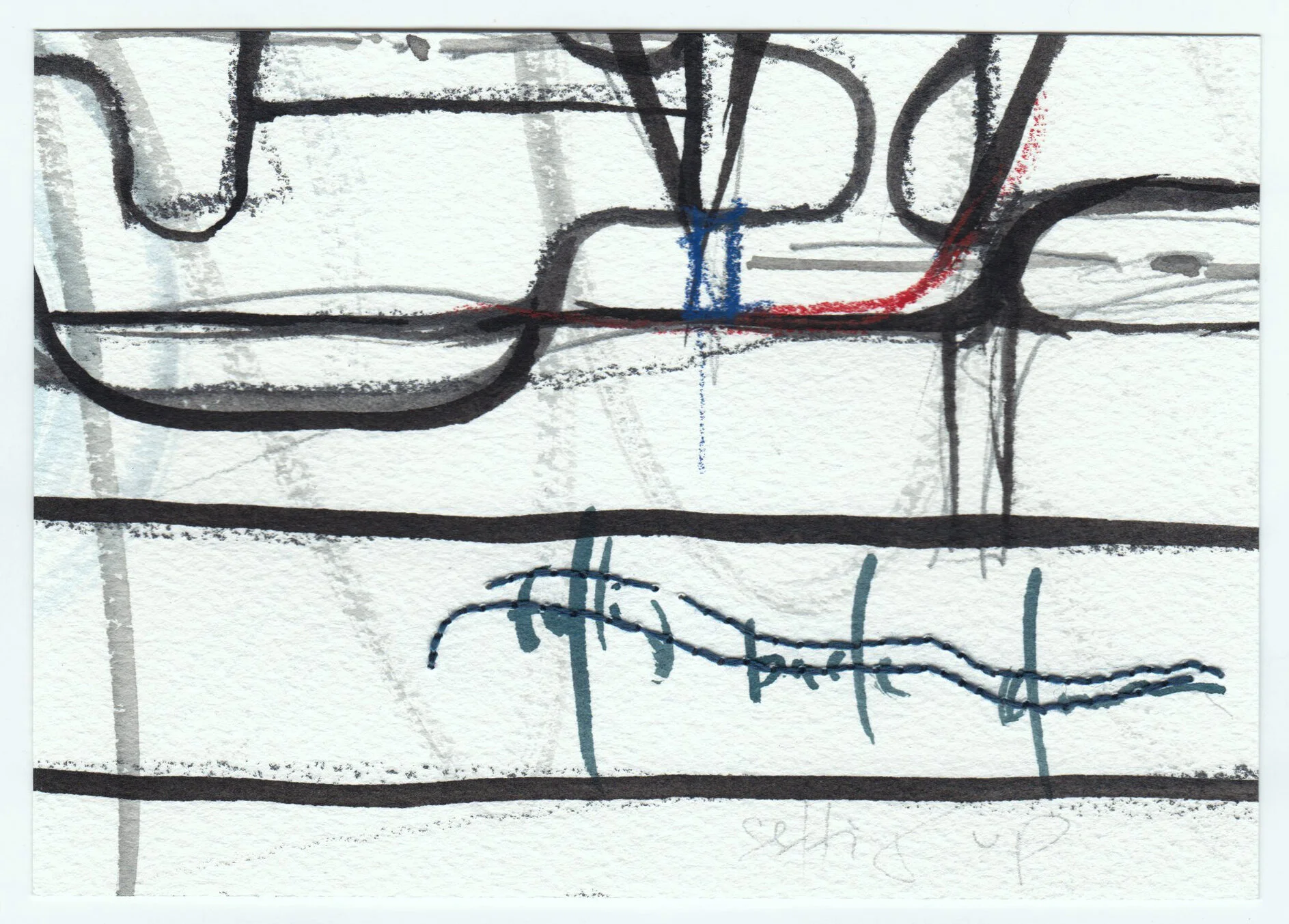

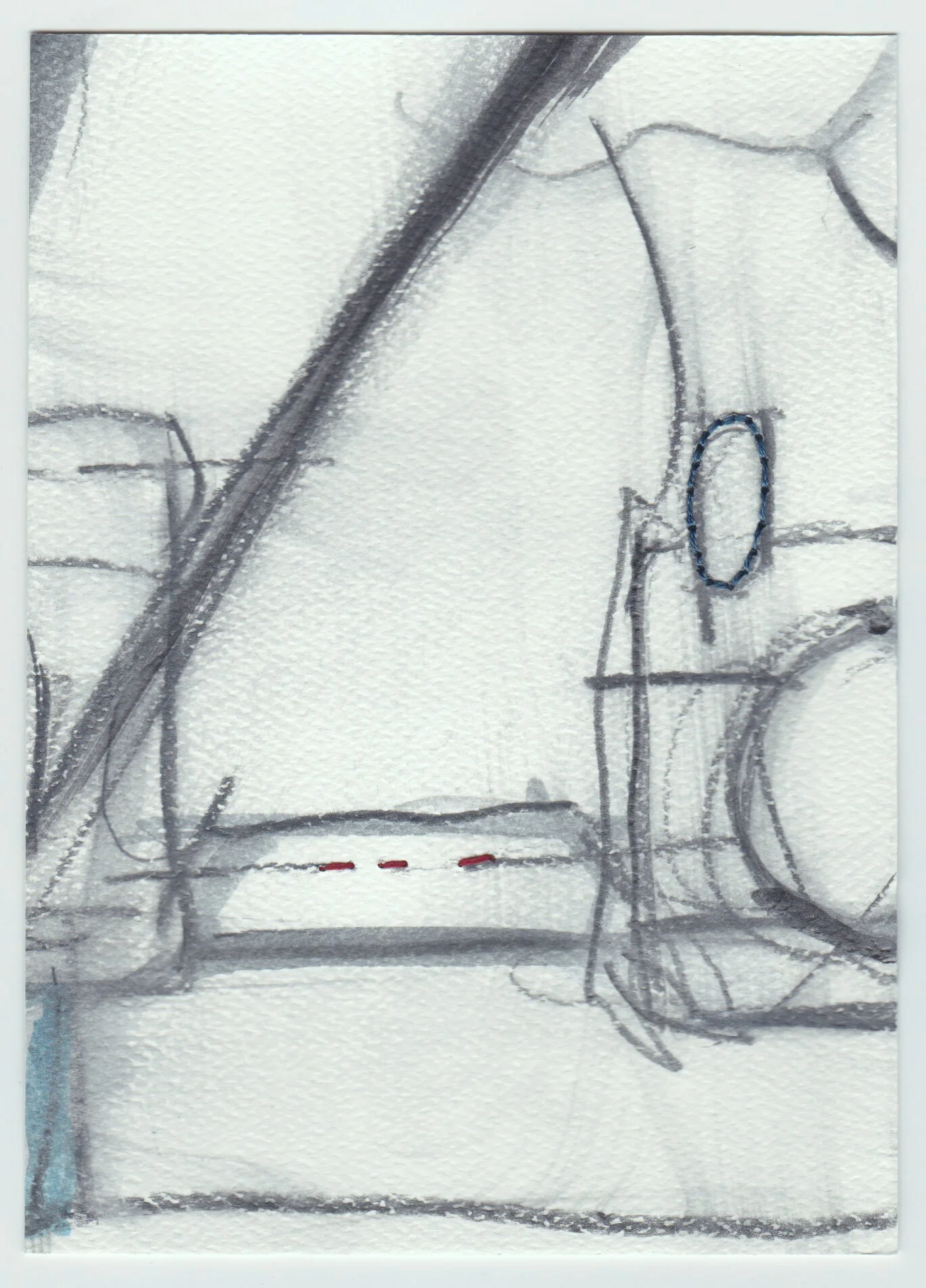

A week ago, a friend and I went for a walk through the markets. We are both equally attracted to the macabre - the blood and guts, insides and undersides of the world - which we knew we'd find here. I wanted to put some art in the meat section. Something to detract from the violence exhibited, a delicate gesture slipped into a scene of meat hooks and mechanical slicers, decaying sheets of tripe, piles of goat hooves, lambs heads with smiles looking like they've been gently put to sleep.

The piece I wanted to place bore the embroidered words, "gritos de cerdos" ("screaming pigs"), which, at that moment seemed appropriate enough. There was even a perfect spot, an empty scale exactly the right shape and size.

But then I started thinking about the person who'd find it. Screaming pigs. How would they take it? Would this not be a hurtful insult, an unfair judgement aimed at someone who more than likely made next to nothing working their asses off in a dangerous and dirty profession, one that simply provided others with what they were used to eating? Coming from a North American white woman who not long ago made her living managing an expensive perfume store? Um, yeah.. that's a load of crap.

So we walked on, deeper into the markets, where the corridors twist and turn in sharp angles, with stalls crammed with tables and chairs, almuerzo (lunch) menus dangling from inner and outer walls.

Then we found Faustino.

My friend is a great deal better than I am at taking pictures of people. He's extremely skilled at putting folks at ease, cutting through their discomfort with his own gut level drive for the photograph, willing to make an ass of himself while using a deadly combination of charm, awkwardness and vulnerability to get it done. In the end, people give in, laughing along with him, in spite of any initial distrust.

Señor Faustino Chambi, unlike most others, wanted his picture taken. When we came into his peripheral vision he was excited about it. He straightened his appearance, beaming into my friend's lens, which opened the floodgates for conversation.. one that happened between Faustino and me in broken spurts, wherein he relayed the history of Bolivia, of which I understood only fragments. But the meaning came out in his eyes, gestures and the cracks in his voice. Then he thanked us for visiting his country.. the first time anyone has done so throughout my experience in Latin America.

So I made him an embroidery. Because one first warrants another.

12/17/15

South...

Warmer, drier, bleaker, dustier, friendlier.. a "wasteland" of smiling faces, graciousness and extreme poverty. After 5 weeks of living inside a crowded canyon, I am blasting out into open space, into a world of half-demolished brick shacks, too-quiet towns, mine ruins and tailings piles, where the ground is so saturated with salt and minerals that it crunches under your feet.

It seems dead here but it isn't. It's easy to assume no one lives here, but people do, trying to survive in whatever way possible. For me, it feels familiar, yet I couldn't be farther away from what I know.

I'm happy to exist in this paradox. It's going to be one hell of a Christmas.