For the last few years -

Since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic - I’ve found myself slowing down and observing the world more carefully.

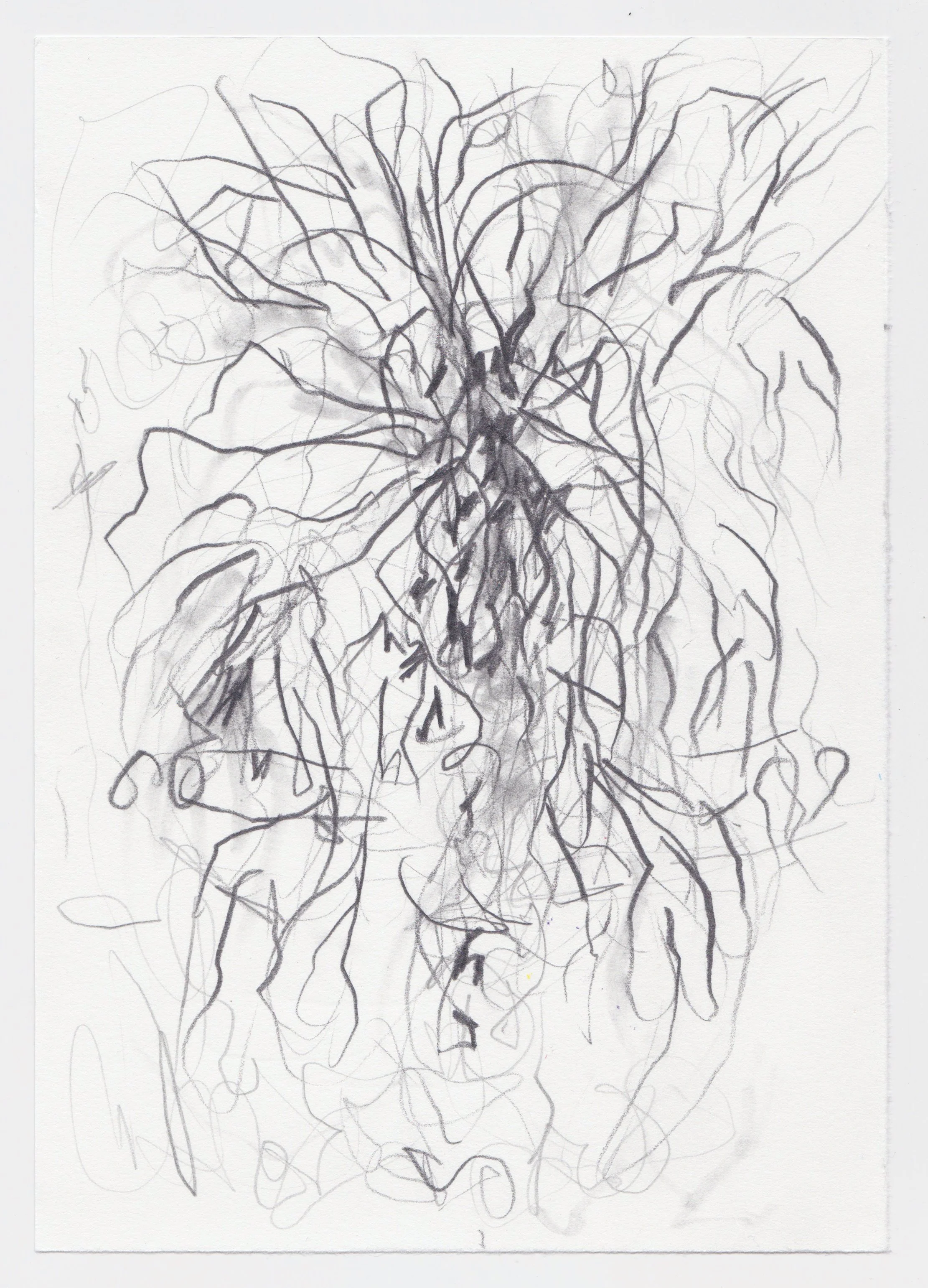

Less motorcycling - more walking. Absorbing details and making drawings with little judgement. Focusing on subjects with a loose hand, letting the marks themselves do all the work. The thing then comes alive in its own right, independent of whatever notions I bring to it.

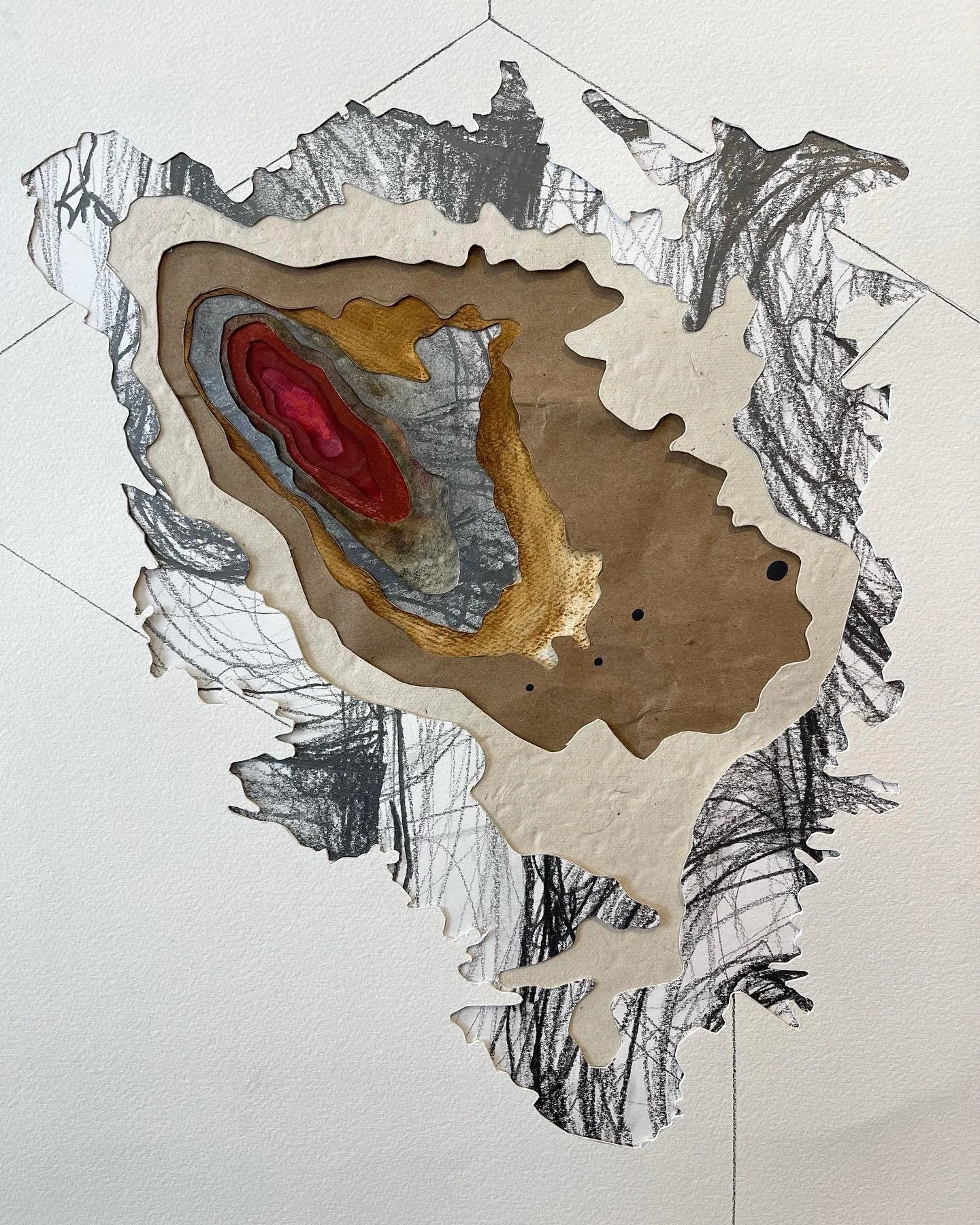

I’ve come to appreciate more the living things that don’t speak. Silent witnesses persisting or even thriving, despite human efforts to contain, channel, extract, extrude, process or break them down, for our survival, comfort or profit.

I notice trees growing around or through barbed wire fences; bolted-down benches and grave markers; roots busting through concrete sidewalk slabs; poison ivy and kudzu that take over, covering and consuming built structures and fixtures. Despite polluted soil, air or water, they hang on, making a mockery of our need for control.

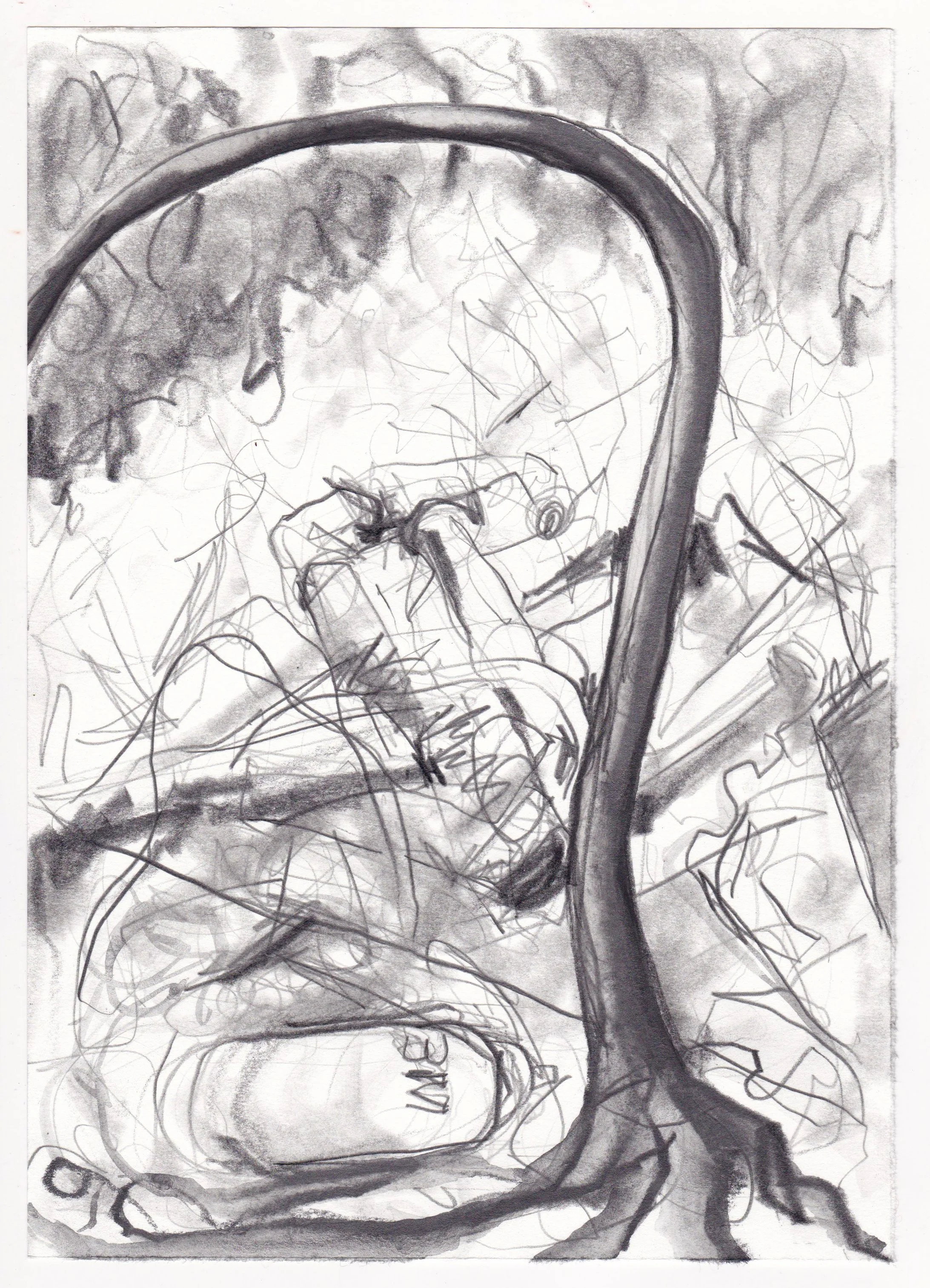

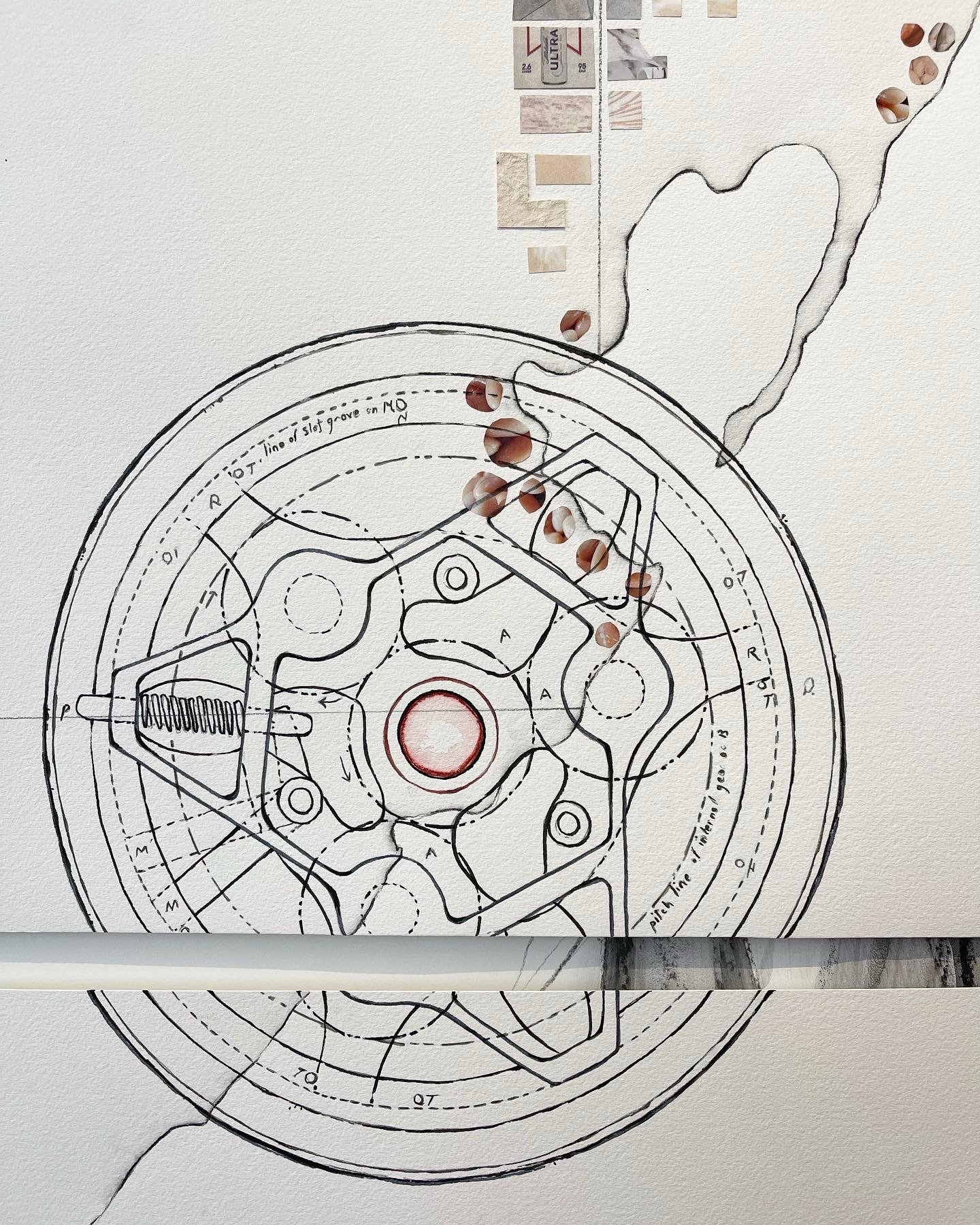

Meanwhile… as the quality of our natural environment deteriorates, we are forever inventing, building, maintaining and replacing technological systems that both mitigate and exacerbate the effects of the climate change they help create. I have to admit, as a motorcyclist, a certain compulsory fascination with such systems. I love their forms and deeply respect the minds required to realize them. I let that fly in my work - and have for many years.

But questions must be raised.

In early May, 2021, I loaded a pack filled with half my body weight in food, water and supplies, then hiked into Grand Canyon via the national park’s Grandview Trail. It was one of several research trips I made as Grand Canyon Artist-in-Residence in an effort to get to know the park intimately. I had no real idea of what I was in for, despite advice given by several experienced Grand Canyon hikers and park rangers. It’s not really possible to contextualize such an experience until one faces the risk..

..and face it, I did.

I have yet to write in depth about my four days down there, and am not sure I ever will. But I’ll say that the physical vulnerability I felt in that short time rivaled anything I experienced during the three continent-spanning solo motorcycle journeys I embarked on for my earlier project, In Search of the Frightening and Beautiful. After my initial descent, I knew that if I didn’t find more water I’d have to cut the trip short and climb out, abandoning my weighty pack for lack of enough energy to carry it back up. My shoes didn’t fit properly and five of my toes turned blue. But I did find an active spring - so I pushed on in the 110 degree heat, skirting the rims of thousand-foot cliffs, marveling at impossible-seeming life forms, bright blooms on tiny cacti, 20-foot agave stalks, red-tailed hawks and the occasional eagle soaring on thermal heat waves rising from the Colorado, still several thousand feet below.

Grandview is one of the steepest, narrowest and most exposed trails into the Canyon. It was sold as an attraction to tourists in the early 20th century after its abandonment as a mining corridor, as the expense of extracting and transporting copper ore far exceeded profits. I chose it to hike because it was the only backcountry itinerary I could get a permit for after waiting too long to apply. But it showed me parts of myself I would never have otherwise come to know. It reminded me that I’m a mammal with a big imagination and skinny legs. But it also showed how strong my will can be. On the fourth day I clawed my way out, over 14 hours, with precious little food or water left, equipment still on my back. My legs could no longer hold my weight, and if my heart were any weaker I would have needed rescuing. But as the chosen artist representative of the Grand Canyon Conservancy, I wasn’t going to let that happen.

My ego wouldn’t stand for it.

The motivation to finish at any cost gave me a glimpse into what I believe drives people to engineer systems that defy gravity, distance and other odds to bring us water, fuel, commodities and just about everything else on the modern supply chain. Aside from any profit motives, it takes an uncanny kind of ultra-determined spirit to solve problems that mechanical infrastructural systems are designed to address. As they age and become strained by growing populations and the effects of a warming atmosphere, greater innovations are required to keep up with emerging crises.

Grand Canyon National Park provides a case in point. Its 50-year-old Trans-canyon Waterline, designed and built to last only 30 years, transports water from Roaring Springs, the park’s single consistent source, through an 8” zig-zagging aluminum tube, to houses equipped with high-powered pumps that shove the water thousands of feet uphill to the North and South Rims. Breaches occur several times a year, causing water rations and $25,000-per-episode repairs. Rather than permanently conserving the water through limitations on park use, GRCA is building a new pipeline and bigger wastewater treatment plants to accommodate the growing needs of its 5+ million annual visitors, and 2500 National Park System and consignment company employees required to take care of them all.

I came to understand personally, through my contact with an unbelievably dedicated group of park workers, that this motivation stems from a deep love of this special place, combined with an intense brand of tenacity and a consequential desire to enable as many people to experience it as is possible. But the question always remains:

To what end?

The type of conundrum I’ve described informs my current work. I think about my own heart - my fascinations, motivations, and limitations in light of the scarier things affecting our world that now feel beyond human control. I love machines. Their sexy-scary precision, power, toughness. How they so often mimic the actions and inner workings of our own bodies. The pleasure and immediate freedom they can bring - the safety and stability they provide that most of us take for granted. But they are also enabling us to kill ourselves with atmosphere-destroying pollution and overconsumption.

Dead or Alive is a byproduct: a single installation that’s part of a growing body of work inspired by environmental conditions in several places I’ve recently experienced (including, but not limited to, Grand Canyon National Park; Laguarres, Spain; the Mojave Desert; and Houston, Texas). On the surface these places have little in common, but the thread that connects their environmental issues (ranging from extreme drought to floods brought on by super storms) seems to be overuse, and consequentially, overdevelopment.

This piece pulls together references from sources I find eternally fascinating: maps related to devastating weather events; aquifer depth topography; schematics of early automobile parts; electrical circuit diagrams; product advertisements repurposed from the endless stream of big box store mailers I pull out of my mailbox; and the image of a single, ancient, domineering tree. I’m after a kind of tension that emerges from between the parts - where they connect and disconnect - the arbitrariness of different relationships set up here, including between the entire assemblage and the space containing it. I want people to look at the surface and imperfections in the wall it’s mounted on, the electrical plugs and switches in the room, the beams or conduits in the ceiling. Nothing here is literal, or even finished. Rather it’s the beginning of something, to be completed in the mind of whomever looks at it, according to their own experiences or desires.

My hope is that it asks,

“Where do we go from here?”

…to be continued…

I owe much gratitude to the Grand Canyon Conservancy, Villa Bergerie, BoxoPROJECTS and countless individuals for generously supporting my research and artwork in recent years. I’m especially indebted to the Conservancy for providing 6 weeks of access to Grand Canyon National Park, its archives, engineering teams, park staff and so much more. Without their help and insight, this work would not exist.